Top 10! Fun On The Command Line

By Bob Mesibov, published 20/06/2014 in Tutorials

If you just love making 'top 10'-type lists but are a little embarrassed to say so, tell people you're passionate about data exploration. To impress them even more, explain that you do your data exploration on the command line. But don't ruin the impression by telling them how easy that is!

In this article I'll do some data exploration with basic GNU/Linux tools and 'one-column tables', by which I mean simple lists. For more information on the commands used here, see their Linux 'man' pages, or ask for an explanation in the 'Comments' section.

Passwords

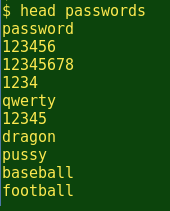

The first list to explore is Mark Burnett's 2011 compilation of the 10000 most commonly used passwords. The list is ordered most-frequent-first, and is one source of the widely known factoid that 'password' is the most commonly used password, with '123456' in second place. Here I've put the list in a file called passwords, and used the head command to show the first 10 lines:

(Burnett explains how he collects his passwords here. Note that he converted all uppercase letters to lowercase in his list.)

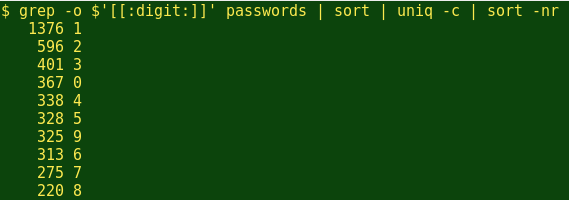

OK, so 'password' is top of the Burnett list. What about individual digits?

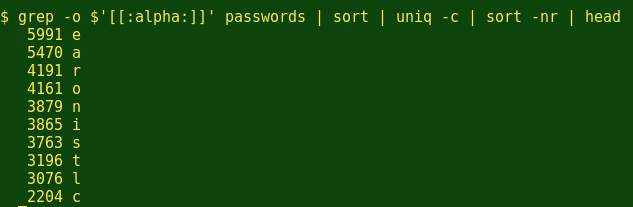

Interesting. The digit '1' appears in the password list more than twice as often as the next most-used digit, '2', and the 10 digits are in numerical as well as popularity order, except for 0 and 9. And the top 10 letters?

The most frequent letters in the passwords file are EARONISTLC. That's not too far off EAIRTONSLC, which is the frequency pattern in at least one published table of letter usage in common English words. Does this mean that most passwords are actually common English words, maybe with a few digits thrown in?

To find out, I'll first convert passwords to a list of letters-only strings, then see how many of those strings are in an English dictionary.

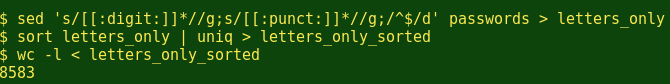

First I'll delete all the digits in passwords with a sed command, then delete all the punctuation marks, then all the blank lines. This creates a list of letters-only passwords. Then I'll prune that list with sort and uniq to get rid of any duplicates. (For example, 'abc1234def' and 'abc1!2!3!def!' both reduce to 'abcdef'.) According to the wc command, my pruning reduces the 10000 passwords to 8583 letters-only strings:

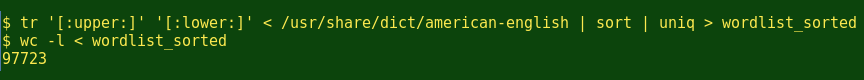

For a handy English dictionary I'll use the file usr/share/dict/american-english, which came with my Debian Linux distribution. It contains 99171 words. I'll first convert this wordlist to lowercase-only with the tr command, then delete any duplicate entries with sort and uniq (like 'A' and 'a' both becoming 'a'). That reduces the wordlist to 97723 entries:

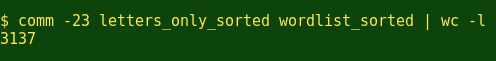

I can now ask the comm command with the '-23' option to compare the two lists and report just the words in the letters-only file that are not found in the dictionary:

The total is 3137, so at least 8583 - 3137 = 5446 'core' passwords in Burnett's lowercase-only list (about 63%) are either plain English words, or plain English words with some digits or punctuation marks added. I wrote at least because a big proportion of the 3137 strings are only slight modifications of plain English words or names, or words or names missing from the /usr/share dictionary. Among the LA's, for example, are 'labtec', 'ladyboy', 'lakeside', 'lalakers', 'lalala', 'laserjet', 'lasvegas', 'lavalamp' and 'lawman'.

Placenames

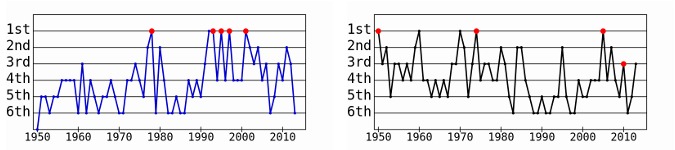

In a previous Linux Rain article, I described how I built a table of Australian placenames with more than 370 000 entries. Using it, I can now answer vital questions like 'Is Round Hill the most popular name for hills in Australia?' and 'Is Sandy Beach tops for beaches, and Rocky Creek for creeks?'

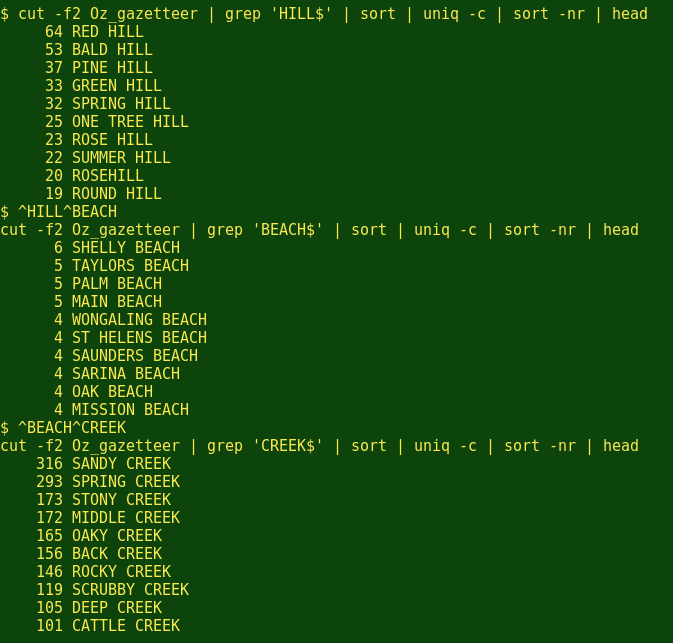

The placename field in the gazetteer table is number 2, so here goes:

Wow. I wasn't even close. (But note how I saved typing by using the ^string1^string2 command. It repeats the last command, but substitutes string2 for string1. Wonderful BASH trick!)

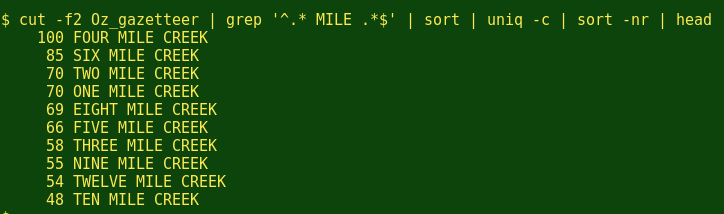

Another burning question is how many placenames there are with 'Mile' in them, like 'Six Mile Creek', and how they rank:

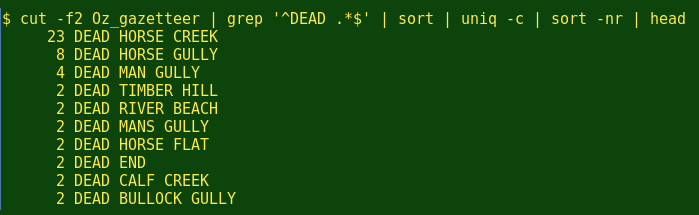

I've noticed a lot of Dead Horse Creeks in my Australian travels, and so has the gazetteer:

Species

The third list to explore comes from a table I published this year of new Australian insect species named in the period 1961-2010. From the table I've pulled out all the 'species epithets', which are the second parts of genus-species combinations like Homo sapiens (you and me) and Apis mellifera (European honeybee).

(Tech note: The insects table, which is available from the open data Zenodo repository at https://zenodo.org/record/10481, includes subspecies. For my 'top 10' exercise I first isolated all the unique genus-species combinations, to avoid duplication from subspecies like Apis mellifera iberica, Apis mellifera intermissa, etc. The final species file has 18155 species epithets.)

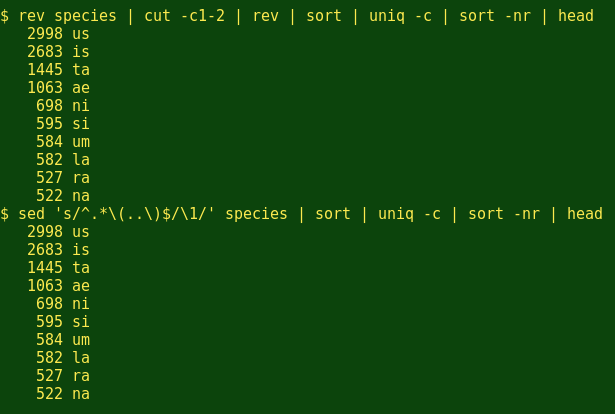

Most people who make jokes about scientific names use the '-us' ending, as in 'Biggus buggus'. What about entomologists? There are a couple of good, command-line ways to get the last 2 letters of a string, and here I've used both:

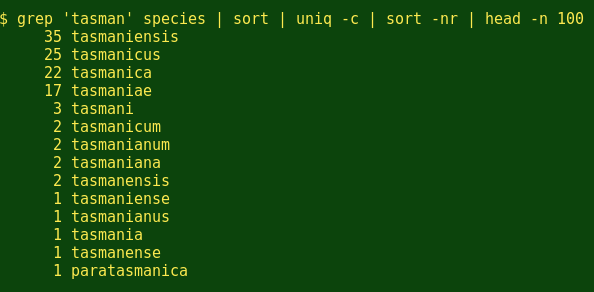

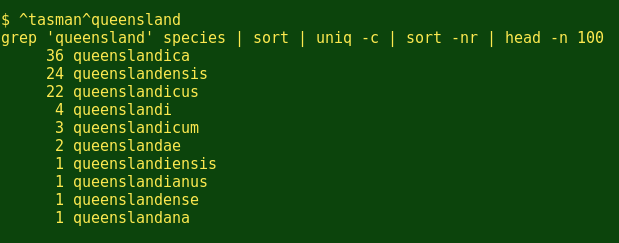

Yep, entomologists prefer '-us', too. Next, I wonder how many species are named for my home State of Tasmania? (Below I ask head for the first 100 lines to make sure I get all the 'tasman' combinations.)

How about Queensland?

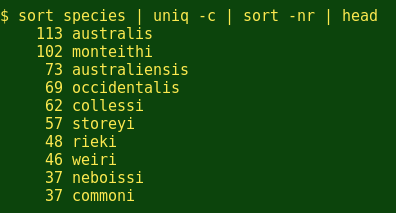

And generally speaking, what are the top 10 names in that insect species list?

Hmm. Apart from the obvious 'australis' and 'australiensis', and the geographical 'occidentalis' (of the west), the other 7 epithets in the 10-most-popular list have been created by entomologists to honour other entomologists. (The epithet 'commoni' honors the Australian butterfly and moth specialist Ian F.B. Common, 1917-2006.)

Speechifying

The commands used above work on simple lists. To make a simple list out a block of text, the command line is again your friend. For example, I've saved a rather filibustery speech in the Australian Senate on 16 July 2014 as the text file hansard. To split hansard into a list of words:

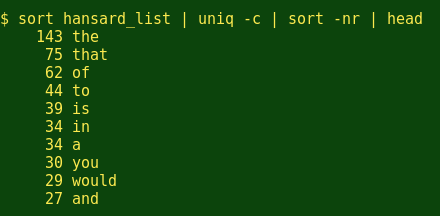

And to look at word frequency in the speech:

Coming soon...

Doing 'top 10' and other rankings from multi-column tables requires a few more command-line tools. I'll demonstrate their use in a future article.